Process

Posted on by Paul DiGian

Process is part of Junior2Senior a course to help you grow as software engineers.

It is about unloading all the knowledge that I accumulate over my career to younger engineers to help speed up their own career.

You can follow me on twitter as well

The book is actually on pre-sale 50% off for only 19$.

Understanding the concept of processes is fundamental when working with computers.

Most articles tackle the issue from a quite shallow perspective or the wrong point of view. We will try to study them from what I believe is the most useful point of view for a senior computer engineer.

What processes are

Processes are a computational unit.

This definition is neither precise nor completely correct, but it helps in understanding.

Whenever you run a program a new process is created. Each software that you are running now in your machine is a process.

Your browser? It is (at least one) process. Your mail client? Another one. Your bash terminal? Yet another process.

Isolation

The most important concept to understand about a process is "isolation". Processes are isolated one from another. One process cannot read nor write memory that belongs to another process. Actually, it is even more strict. One process can write and read, only the memory that belongs to itself.

The difference is that a process cannot access memory that belongs to no-one. It can access only its own memory.

If the isolation is not respected and a process tries to read or write (access from now on) memory that does not belong to itself, the process is forcefully terminated by the operative system with a segmentation fault.

All the time a segmentation fault is thrown, it means that the process did not behave correctly and it was trying to access memory that didn’t belong to it.

Isolation is the greatest advantage of processes. It assures that the content of the memory never changes under your feet and that you are the only one to have access to the memory.

While this advantage doesn’t seem particularly interesting, and maybe also bland, modern (complex) software takes full advantage of it.

For instance, Redis (a NoSQL database) use a single execution unit to avoid coordination keeping the software extremely fast. The alternative would have been to use thread, hence more execution units, and to introduce locks and a great deal of complexity in managing multiple execution units changing a shared memory.

Modern browsers, have one process for each tab. This avoids malicious code to gain access to data in other tabs. The use of multiple processes, one for each tab, makes it impossible that javascript code running in a tab from a pishing website, can access any data from a tab from your bank.

Isolation is a wonderful capability, but it comes at a cost. Software, to be useful, need to read input and produce output. So a process needs some way to get input from the outside world and to push its output.

Introducing IPC or Inter Process Communication

Inter Process Communication

We discussed how processes are isolated, we agree that isolation is a great capability for processes, but that it comes at a cost. It makes difficult input/output. We are now introducing how processes can communicate with each other and with the outside world.

We will have a different section for each of the IPC methods we are describing, so the discussion on this page will be rather short.

For maintaining isolation is important that it is always the process to drive the I/O. It can not happen that some data change without the process having asked it explicitly. This is in stark contrast to what happens with threads.

Using threads it is possible that some value changes without one thread explicit permission. So a thread could read a variable, do some other work without ever writing anything to that variable, and then find the initial variable changed. Another thread, in the same process, changed that variable. This is a source of many, very complex to reproduce and to address bugs. And this does not happen between processes. Of course, there is an exception to this general rule.

We will now explore the most common IPC methods, starting from the most useful.

Sockets

Sockets are extremely important IPC methods. They allow communication between processes that reside on different machines or on the same computer. For instance, you used a socket to download this article from the web and read it.

The interface for sockets is relatively simple. You start by establishing a connection and then you can read data from the socket or write data into it.

More practically, when you establish a connection with a socket, the operative systems give you back an handle for the connection the handle is called file descriptor. (We will study why it is called a file descriptor, so subscribe to the mail list or follow me on twitter.) After you get the handle, you create a buffer of memory.

To read from a socket, you pass the socket handle and the buffer to the operative system using the read system call.

The operative system will first interrupt your process, then it will fill the buffer with data, and then it will resume the execution of your code.

Now the buffer contains the data read from the socket and you can act on it.

To write to a socket, you do the inverse operation.

You fill your buffer with data. You pass the socket handle and the buffer to the write system call.

The operative system interrupts your process, reads the data from the buffer, moves the data to the other end of the socket, and finally resume the execution of your code.

There is much more to study about sockets and I will write about them shortly.

Signal

A less versatile way for processes to get information from the outside world is signal.

Signals are short messages sent to a process, each signal has associated a default action. The default actions are to:

-

Terminate the process

-

Ignore the signal

-

Terminate the process and write possible debug information (dump the core).

-

Stop (temporarily) the process

-

Resume the execution of a process stopped earlier.

A signal can be sent from one process to another and can be caught from the process and acted upon.

For instance, several systems catch SIGHUP to reload their configurations. Other systems catch SIGTERM (Ctrl-C) to terminate cleanly the execution and not lose data or important information.

Some signal (SIGKILL and SIGSTOP) cannot be caught, nor ignored, and they just kill the process without giving it the possibility to exit cleanly.

Files

Files are another great way to communicate between processes. One process can write in a file, and another could read from it.

The interface to work with files is exactly the same to work with sockets.

You acquire a file descriptor first, then you create a buffer, and finally, invoke the read or write system calls.

This similarly would give a hit on why the socket handles are called file descriptor. Underneath they are the same.

Using files for IPC allows processes to communicate between the same machine, they both need to have access to the same file.

Files come also with another complication, there must be coordination between write and read operations.

Locks and semaphores are used in these cases.

A great way to use files are IPC is to use tools like SQLite. SQLite can write and read directly from a file and it takes care of all the coordination for you. An application can write data to an SQLite database, while a second one consumes data from it. This approach works great even if it is difficult to receive notifications of writes.

Shared Mapped Memory

The final and most complex way to IPC is mapped memory.

This method is not that different from using files but does not rely on an explicit read and write calls.

It is quite dangerous because allow data, in the share mapped memory, to be changed implicitly by another process.

The data that you read from it, now and in the future, maybe different even if you never changed it.

You can create a shared mapped memory invoking the mmap system call passing the appropriate flags.

Other processes can do the same.

At this point, processes have access to a memory buffer that is shared between them.

What a process writes in the buffer can be read by the others.

Notice how this is the only method that allows implicit changes to the memory owned by the process.

With all the other methods you provide a buffer that it is changed when you ask so, using the read system call.

With this method, the values stored in the shared memory can change under your feet.

There are more IPC methods but the one provided is an interesting overview, much more than enough to get started.

We continue this chapter on how to work effectively with processes in a Linux system.

Start a process

There are few ways in Linux to create another process.

The most used one is the fork system call.

It creates a copy of the actual process and starts to run it while the original process keeps running.

The fork system call returns a different result on the "parent"/"original" process (it returns 0 zero) from the "child" process (it returns an ID greater than zero).

Detecting the return value of the fork call is possible to distinguish between the child and the parent process.

The clone system call is similar but allows for more control.

It is a more advanced function and it is used in the implementation of container technologies.

It also returns the ID of the new process.

Another related function is execve it does not create a new process, but it executes a new program in place of the original one.

It is not strictly related to this topic, but, together with fork is enough to implement a simple shell (like bash or sh or fish).

Process identification

We saw how to start a process with the fork system call, and we see that fork returns an ID.

Since the ID identifies a Process, those IDs are called PID, for Process ID.

The number of PID is limited, they are stored in an int, so in systems running for a long time with a lot of processes starting up, the PID will get recycled.

However, at any given time, a PID identifies one and only one process.

Knowing the PID of a process is possible to interact with it. Sending it signals or attach it to a debugger.

The simplest way of knowing the PID of a process is to store it when you create it. Of course, it is not always possible since you may need to know the PID of a process not created by you.

Fortunately, there are other ways to know the PID of the processes running in the system at any given moment.

All those methods rely on reading data from /proc.

Inside /proc there are several directories, one for each PID, in the form /proc/[PID], listing them is a simple way to know which processes are running in the system at any given moment.

To list the process we can rely on bash globing with.

$ ls -lna /procThis will show a lot of directories. The numeric ones are the PID, while the others are for system information.

Inside those directories, there are a lot of files with very interesting information.

For instance /proc/[pid]/cmdline contains how the software was invoked.

/proc/[pid]/exe is a symbolic link to the executable that is running and /proc/[pid]/comm contains the name of the software.

Fortunately, we don’t have to rely on manually parsing the content of the /proc directories since different utilities are available for us.

The ps utility allows to list all the processes running in the system, it is useful to identify the PID of a specific software running in the system.

I am writing this article on nvim so if I want to know the PID of nvim I could run:

$ ps -e | grep nvim

27188 pts/1 00:01:08 nvimAnd this will show me that the PID of this instance of nvim is 27188.

Another way to use ps is to pass the aux options, this will show more information. Information like the arguments that were passed to the program.

$ ps aux | grep nvim

pgian 27188 3.4 0.1 129616 13764 pts/1 Sl+ 17:49 1:29 nvim content/posts/process.asciidoc

pgian 27518 0.0 0.0 14752 1028 pts/2 S+ 18:32 0:00 grep --color=auto nvimWe can see the user, the PID, and the command-line invocation of the software.

Notice how this shows also grep indeed, grep is matching its own invocations.

While ps is great for quickly get to know the PID of a process, it is not very ergonomic when exploring a running system.

A better alternative in such cases is htop.

htop allow also to sort the processes in a system to visually show the processes tree.

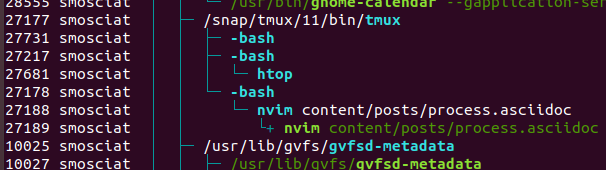

Here we can my setup as I am writing the article.

I am running the software inside tmux (PID 27177), which in turn, runs 3 bash command lines (27731, 27217 and 27178). In turn, one bash shell runs nvim again with PID 27188 and another is running htop (27681).

We started talking about processes, we talk about isolation and why isolation is fundamental, we discover that isolation is great, but we need to do input and output. Then we study some Inter Process Communication (IPC) mechanism. In this last part, we studied how it is possible to see all the processes running in the system with tools like ps and htop.

In this last part, we will understand the state of a process. At the very beginning, we describe processes as a computational unit. Modern computers can run a lot of processes at the same time, while I am writing this, I have 285 processes running. However the number of virtual cores in a computer is limited, my machine has only 4. So how 4 cores can run 285 processes?

Of course, not all processes run at the same time. Some of them sleep.

Process State

It is not necessary for software to keep running continuously. If you are reading or writing from a file descriptor your CPU does not need to work. The CPU is waiting for the IO layer to finish, either against the disk or against the network. In this case, the process is sleeping.

On the contrary, when the CPU is working, for instance, it is summing numbers, creating strings, doing some math operations, moving memory, the process is running.

Besides the sleeping and the running state of a process, there is a third state, the ready state.

A process is in the ready state when it has done waiting, for instance, the disk finally finished returned some data, but it is not yet running, because the operative system has not allocated yet resources to it.

Recap

In this chapter, we study processes. We understand what they are and one of their most important features, isolation.

Isolation is great, but software needs to communicate with the outside world, hence several Inter Process Communication (IPC) mechanisms are available. We study briefly, sockets, signals, files, and shared mapped memory.

Then we study how to start a process and how to identify processes in a running machine.

We interact with the raw tools that the operative system gives us to query processes and then we upgraded to work with more refined tools like ps and htop.

Finally, we understood what is the state of a process and what are the main states a process can be in, sleeping, running or ready.